The primary purpose for my fancy new toy is to be able to cover greater distances in a shorter period of time. The Super Cub is obviously superior than the PA-11 with 36 gallons of fuel instead of 18 and 150hp instead of 100hp. Cruise speeds are 100-110mph, instead of 70-75mph.

When it comes to glaciers of Europe, Turkey, and the Caucasus, speed and range are primary elements, as no mountain peak except one is higher than Mt. Blanc, which I have already conquered with my supposedly anemic little airplane. While there is not a need to climb higher and to do so faster in my present locale, glacier ambitions in Alaska, the Yukon, the Andes, and the Himalayas all require vastly higher altitude than my little desk fan powered Cub can achieve. The book says the PA-11 can climb to 16,000 feet, whereas the Super Cub supposedly can get somewhere between 19,000 and 21,000 feet stock.

It was time to put the new toy to the test, which was done with a flight to the Matterhorn (14,692’) and Dufourspitze (15,203’), the latter of which is the highest peak in Switzerland. Keep in mind that I have already surmounted these peaks in August of 2018 with the desk fan, so the exercise would be merely comparative to record time, rate of climb, and oil temperatures.

The process is simple: record what time it is and the oil temperature at each thousand-foot interval. I can then back into FPM (feet per minute) climb rates and plot them on a chart. My purpose in doing so was to allay nerves, as I often find myself neurotic in challenging terrain, wondering over and over if oil pressure was this low, temperatures this high, airspeeds this low, etc. the last time I was here. Is there an oil leak? Is the engine running too hot? Is the fuel reading lower than it should? Did I just smell some fuel? Is there a leak? Where is the nearest airport? Oh wait, its fine now. Was it like that the last time? Oh look, a pretty picture! [Forgets about the engine]

It is more expedient to have recorded data than to waste bandwidth on neurosis, which is why I decided to record the first climb to a minimally reasonable altitude of 15,000 feet.

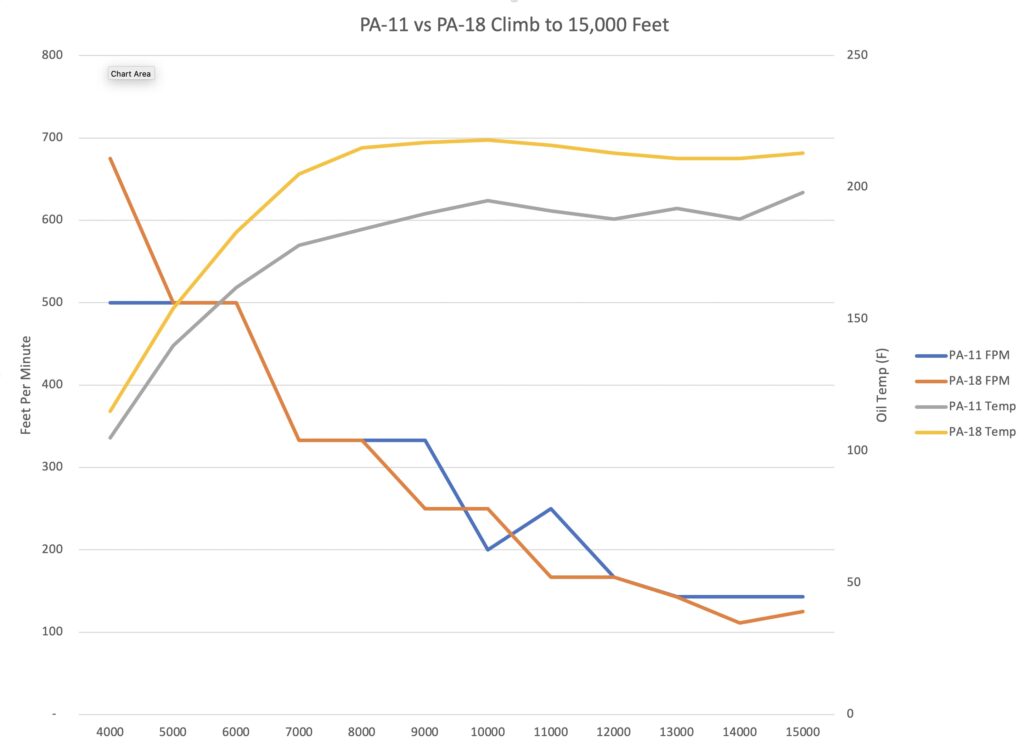

My new toy is somewhat impotent. It does not climb very well at 15,000 feet. In fact, in the cockpit, I dare say it climbs about the same as the PA-11. The following chart, which overlays a similar climb test on a hot day in June shows that the Super Cub, on this flight, was a bit slower, which is positively dismal, given that airplanes fly significantly better in the cold.

Declining lines are the climb rate as the airplane gets higher. The ascending lines are oil temperature as the airplane climbs. PA-11 vs PA-18 is noted in the legend.

After landing, I began corresponding with an individual that operates a Super Cub at ridiculous altitudes in the Andes. The first takeaway was that it might serve me well to read the manual, which I then did, finding that I am not leaning enough and that I was excessively neurotic about redline oil temperature. I have an electric oil temperature gauge, which merely turns red at redline (without indicating exactly what that is) and stays green until then. Analog gauges show the temperature limit on the instrument. For the Lycoming O-320, it is 245F, whereas for the Continental O-200, it is 225F. At 218F maximum oil temperatures in climb, I thought I was on the edge of redline, when Lycoming ever so kindly notes that 180F-220F is a normal range for cruise, much less climb.

That implies that I have more potential to lean the engine. As a carbureted engine with fixed timing and manual leaning (all of which is computerized with cars), leaning is an exercise to save fuel plus gain power at high altitudes. The cost is heat. If the heat is excessive, it can fry valves and lead to a shortened engine life span. In the process of even proper leaning, oil will run hotter, which was the byproduct I was aiming to keep in line (with my flawed assumptions). The PA-11 only has an oil gauge, so I lean using its noticeable RPM peak as well as eventual oil temperature.

Clearly, I need another test run, this time leaning it as much as I can, while also running a steeper climb, with less airspeed. That will cut some time off, though it also adds to heat. In any case, all of it is part of a very, very long troubleshooting and engineering process so I can configure a Super Cub to fly to 23,000 feet someday, or just to 18,510’ at Mt. Elbrus, if the Russians will let me in.

The Valais, on the way to the Matterhorn.

Turtmanngletscher with Bishorn.

Northern ridge of Schalihorn, with Dufourspitze on the rear left.

Southern slope of Zinalrothorn (13,848′). At this point, I am dismayed that I am not higher.

Monte Rosa Massif. Tax haven left, mafia right.

Dufourspitze (15,203′) with Italy in the background.

I guess these are foothills. It sure looks it from 15,000 feet, although there are a few glaciers down there so its higher than it looks.