Seventy-five years ago, on June 8, 1949, N5547H rolled off of the assembly line in Lock Haven, Pennsylvania, equipped with a wood propeller and a 90-horsepower engine. Some nondescript individual gave it a 30-minute test flight, and yet a different individual flew it for five and a half hours to York, South Carolina.

I found out this information in late 2010, after taking ownership of the airplane. I had just begun doing business with a firm not far from downtown York, South Carolina, and wondered what happened to the airplane in the gaps that the logbook showed in its later history. Seeing a private field registered outside of York, I phoned up the owner, Ed Currence, in January of 2011, and asked him if he knew about a plane that might have been there over sixty years ago. “Oh, that plane was owned by my father’s business partner, Max Mullis. There was another airfield, which is closed now, that they used.” Ed went on to explain that he still uses the building that his father had alongside Max’s business.

The airplane was part of a crop-dusting operation, which ran from 1946 until possibly 1957, when Max left for Florida to start a marina. Back then, Max was the only crop duster in town, and they used “the real stuff”….DDT. The story is backed up with the receipt of an agricultural airworthiness certificate in 1951. My grandfather would snarl about dealing with a DAR in 1996 to get a standard airworthiness certificate.

I received permission from Ed to land at his field in York, and I used it a few times to shave a few minutes off the long drive from Charlotte, North Carolina, literally flying the same plane, to the same town, 60 years later, to perform consulting work. At the time, it had no starter, transponder, radio, or electrical system. When asking my grandfather why he didn’t add a few convenient options to the airplane, he would reply with either “have you heard of a thing called weight?” or “they didn’t have any of that back in the day.” What did this mean for my commute to York in the 21st century? I’d have to hand crank the prop, hop in, and skirt the Class B “cake” around Charlotte-Douglas Airport.

I finally connected with Max’s son in the Florida Panhandle over a year later. He filled in a few blanks, that Max had a Piper dealership, “used to crop dust from Florida to Pennsylvania,” and he used to “draw a line on a map and fly the line looking for landmarks,” which he taught his son to do. The irony is that, in 1990, my grandfather would teach me in a separate taildragger to navigate by roads. “What about a map?” “Now there is no need for that. You know where the highways go.”

The PA-11 went to Florida with Max, who later died in 1977. His flying days must have ended a few years before that, as the plane shows up in the low country of South Carolina in the early 70s, with a few inspections before the trail goes cold, at least as far as the logbooks go, in 1974.

My grandfather purchased the airplane, not far from its last inspection, in Florence SC in the late 80s. It was “derelict” and in storage with the engine and “one good and one bad wing” as he put it. The airframe would go to his winter residence in Florida, and the “bad” wing went north to New York, where it would torment me starting age 8, sitting there, year after year, untouched as he restored various other airplanes that one day flew and left the coop to new owners. “Grandpa, what about that one?” I would ask. “Oh, that is the PA-11. Your father wants one” was the reply I would get year, after year, until the wing came down from the rafters and went to Florida.

In 1996, the PA-11 flew again, fully restored by my grandfather, who made no shortage of announcements about how much money he spent in parts to restore it. He took quite some extra special care ensuring it had a freshly overhauled Continental O-200 (which survived the fury of Hurricane Andrew in 1992, coming off another Cub that was destroyed by the storm). It had overhauled mags and an overhauled carburetor. It was the 90s, when chrome cylinders were all the rage, which corrupted my thinking until a quarter century later, when I discovered the glory of merely buying new ones from the factory.

When I was 15 years old, I spent a few weeks in Lake County, Florida flying with my grandfather from his borrowed airstrip, which was a field filled with cows from the rancher that owned it, a ditch that had a habit of washing out the culvert every time it rained, and a power line dangling 14 feet above it. He wanted to give me unofficial lessons, convinced that a prospective instructor in New York would “want to milk it flying around for nothing” so “we need to get you tuned up.” That meant doing takeoffs and landings on this little patch of danger, buzzing the cows out of the way, skipping over the culvert, and landing under the power lines. I’ll never forget it.

In the summer of 1997, my grandfather trucked the airplane to New York, put it together, and announced that it is the airplane I would be taking lessons in. “But what about your [1990 model year, brand new] Super Cub? It is better.” “That is my pride and joy. You’re not touching it.”

He struggled to find an instructor, as the airfield was less than 1,500 feet long, with power lines on one end, and it unnerved the first few that he asked. He found a cantankerous old bastard, who first wanted us to fly the plane to a public airfield for lessons, for which my grandfather bent to his will and got him to agree to instruct from our airfield. I guess it is a testament to my grandfather’s old school methods that I failed to notice that the instructor was difficult. Other students later would tell me how utterly harsh he was. That got me to thinking about that one time in a Cessna 150 that he let me accidentally spin it in an uncoordinated stall, intentionally to “teach a lesson.” “What an asshole!” someone replied when I told them the story. I haven’t spun since, so perhaps it was good teaching?

Anyhow, I soloed in September 1997 (after 4.3 hours of instruction, so the unofficial lessons worked) and later got my private license in the PA-11 in 1998. I had a few years of incredibly memorable flying on warm evenings, on fall days, with the door open, in the middle of winter, around lake effect snow, in lake effect snow, above lake effect snow…you name it, I found a way to do it.

My father had owned the plane during my training and himself soloed in it, then lost interest. It would largely sit from 2001 until he died in 2010, before I took the reins and brought it back to life.

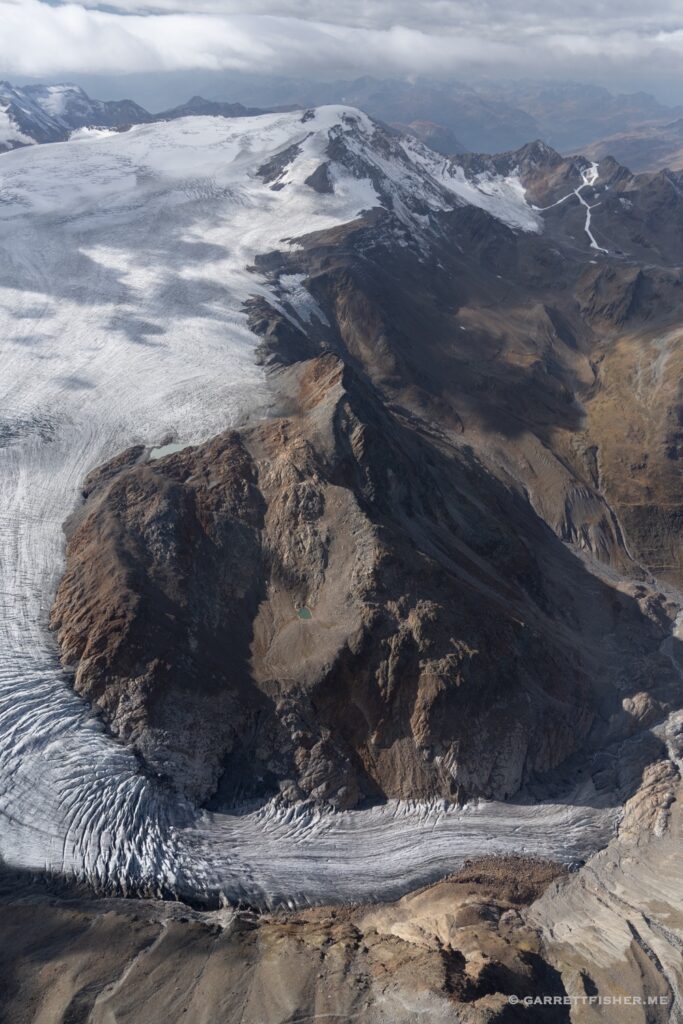

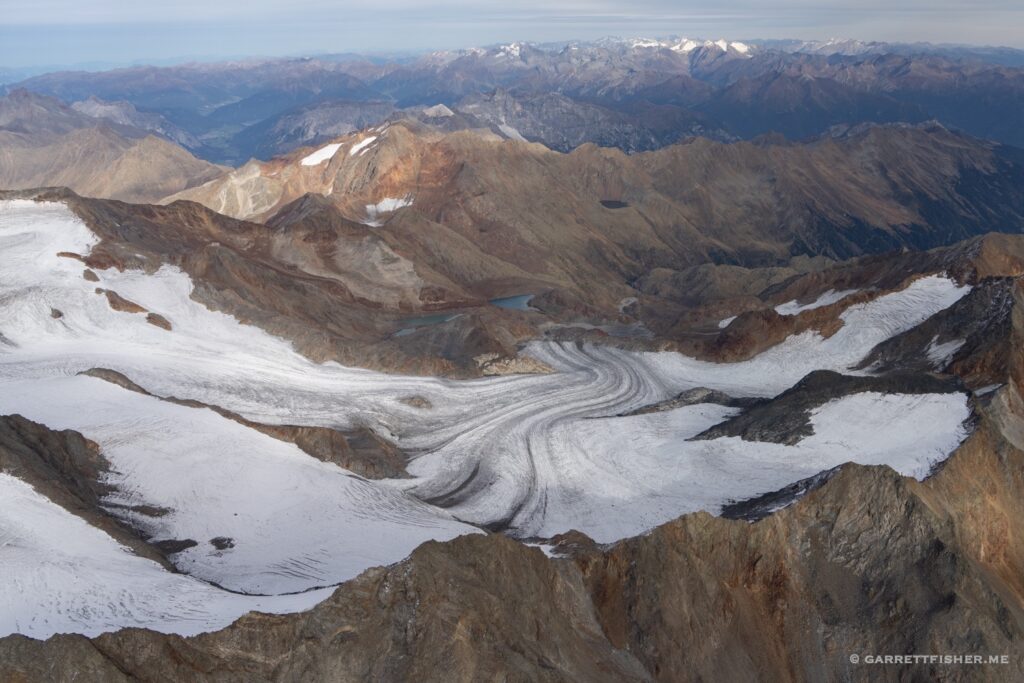

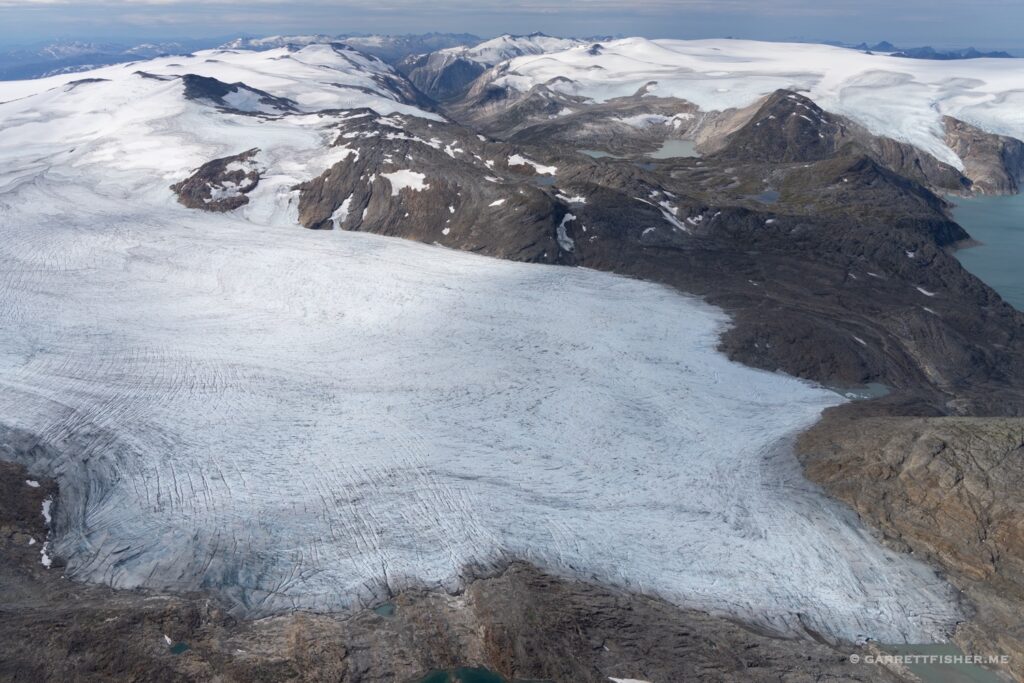

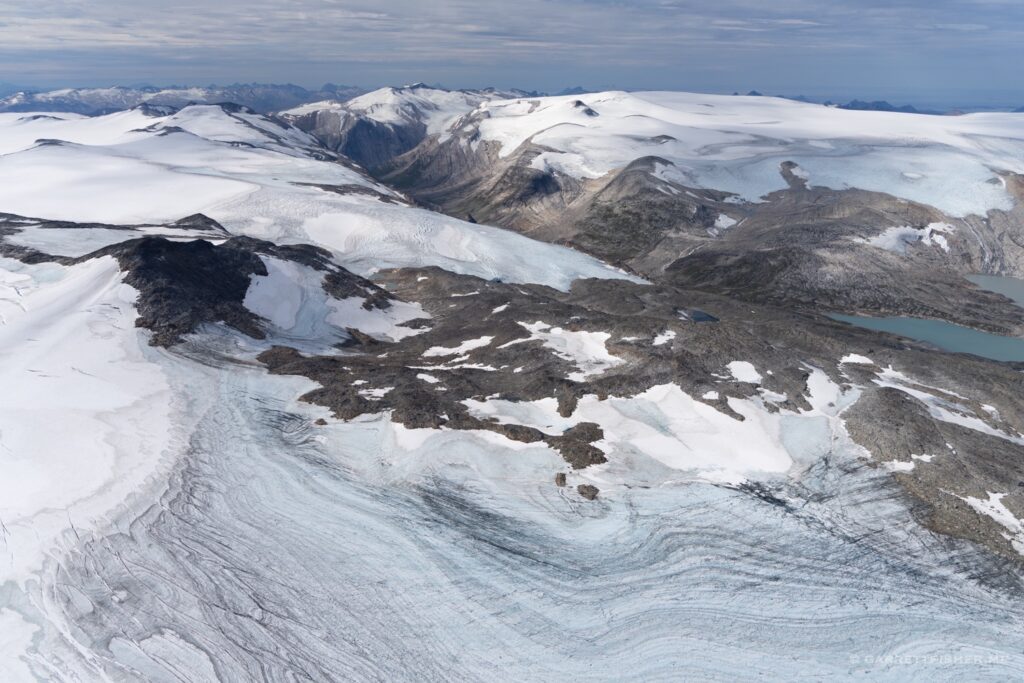

Since 2010, it has flown 10 times more than it did from 1997 to 2001. For anyone that has followed the blog and my personal history, it has flown from New York to Florida, and the Outer Banks of North Carolina to the Great Salt Lake, and from New Mexico to the convergence of Montana, Alberta, and British Columbia. In 2016, it was shipped to Germany associated with our move to Europe. It has been based in New York, Florida, Charlotte North Carolina, the Outer Banks of North Carolina, Leadville Colorado, Alpine Wyoming, near Frankfurt Germany, the Spanish Pyrenees, the coast of Portugal north of Lisbon, and two places in Switzerland. It has flown to 26 US states, 12 countries, 5 time zones, 2 continents, and has been to the highest mountains in the Appalachians, South Dakota, Wyoming, Montana, Colorado, Utah, Switzerland, France, Italy, Austria, Germany, Liechtenstein, Andorra, and the Pyrenees and has been used to photograph every glacier in the US Rockies and the Alps.

The move to Alpine, Wyoming meant the addition of a radio. The jet guys would not have it that some Cub was wandering around while a Citation was on approach, wedged between terrain. I added vortex generators that summer for safety reasons. Later that year, a transponder, electrical system, and starter were added to make it ready for Europe. In 2019, I added a wind-driven alternator and USB ports, which made life much more convenient. In late 2022, it received nav and landing lights, to allow for enjoying the moments after sunset and before the airport closed for the night during winters in the Alps. For those that read my winter rampage, it has factory new cylinders.

It is tempting to ascribe a sense of emotionality to an aircraft. One assumes, due to the passage of time, the heights the plane flies, and the fears or fatigues of the pilot that the plane is going along for the emotional ride that is the flying experience. The reality is, for all the worry and wonder that accompany the awe of flying such an old and slow plane in such places, that the aircraft does its job and is absurdly consistent. The engine starts on three cranks like it did in when I was a teenager. The oil temperature is the same depending on the power setting and outside air temperature, and she flies like she always has, no matter where it has been flown.

The plane not only makes decades of flying possible, with all of the destinations and stories involved; it seems to be a vessel for the stories of the people that fly it, from Max Mullis to an unknown owner in between, my late grandfather, late father, and now me. I often wonder how we’ll view airplanes like this when they turn 100, or 125, or older than that. Sure, they will get rebuilt, though there is no reason it can’t keep flying into the 22nd century, which is what I hope for and will do my best to contribute to happening.

Far too many PA-11 photos below, though they happen to be the ones I could scrounge up that best tells the story of its journey in almost the last 25 years.

1997. Lake County, Florida. My grandfather hand cranking while I hold the brakes.

2010. Pulling the airplane out of storage at Fisher Field near Buffalo, New York. It is tipped on its nose to cause oil to spill forward and prime the pump, as it hadn’t been started in years. She still started on three cranks!

2013. Huntersville, North Carolina, its home for a few years. Landing just before an explosive snow burst.

2014. An early July morning in Leadville, Colorado, where it was based for almost a year.

2014. Lincolnton, North Carolina. Next to another PA-11! Only 1,500 were ever made.

2015. Alpine, Wyoming, after having flown it from the Outer Banks of North Carolina, nearly killing myself twice in the process.

2015. Alpine, Wyoming, parked in front of the house. The glories of an airpark.

2015. Rock Springs, Wyoming. Parked in front of a Boeing Business Jet.

2015. Double L Ranch in the Star Valley of Wyoming. In a phenomenal act of stupidity, I nearly ran it out of fuel five minutes before Alpine and had to land at a private field. Dumb.

2015. Alpine, Wyoming. About to take what would be an unforgettable flight above the clouds, around Grand Teton, in 35 kt winds.

2015. Alpine, Wyoming. Disassembled for shipping to Germany.

2016. Egelsbach, Germany. In the Fatherland! Who ever would have seen that coming?

2016. La Cerdanya, Spain. Just like that….out of the Fatherland. Didn’t see that coming either, but some application of logic would lend a person to conclude that life in Germany was a bit too…rigid.

2017. La Cerdanya, Spain. Just landed after a lightning bolt went whizzing by.

2017. Bagneres-de-Luchon, France, in the Pyrenees.

2017. Carpentras, France, not far from the lavender fields of Provence.

2017. Castejón de Sos, Spain in the Pyrenees. A lovely little field.

2017. La Llagonne, France, at over 5,000 feet in the Pyrenees. I needed a “licence du site” to land there.

2018. Cáceres, Spain. The Guardia Civil pounced with four officers and searched the plane for cocaine, convinced I had snuck it in from Morocco. After a bunch of arguing, they took selfies and waved as I flew to the Portuguese coast.

2018. Casarrubios, Spain, southwest of Madrid.

2018. Sion, Switzerland. Amen!

2018. Engadin Airport, Switzerland.

2018. Gstaad, Switzerland with other Cubs during the “Tour de Cervelat.” I thought the airport was public use and showed up without the proper PPRs. The staff were incredibly nice about it and I loved the energy at the airport the moment I stepped out of the plane. I didn’t realize then that it would be the future base for the PA-11.

2019. 4x4ing in La Cerdanya, Spain.

2019. Coscojuelas, Spain, at the base of the Pyrenees.

2021. Zweisimmen, Switzerland. Headwinds caused such a delay getting back that the airport closed, so I diverted to one that was open. I found out I parked in the wrong spot, as the hayfield is owned by a farmer.

2021. Innsbruck, Austria, during the Alps glacier binge.

2021. Barcelonnette, France in the southern Alps, also during the glacier binge.

2021. Bolzano, Italy, before diving into the Dolomites.

2022. Gstaad, Switzerland. In semi-retirement now that I take the Super Cub to the far flung places instead.