It is evident that my standard photography day is one with as sunny of a sky as possible. While I continue to surprise myself with the errant beauty of sky texture as it unpredictably presents itself, instinct takes over, and I am back at it looking for blue sky. Every now and then, I decide to toss personal convention to the wind and go up for a “classic” flight with muted overcast tones.

I held onto this “classic” idea for a while until it occurred to me that its patently false. There is nothing “classic” about it, at least when it comes to aviation, mountains, and photography. How many times have I gone for this pseudo-traditional flight in the mountains with muted tones, beckoning the reflective aura of Bach’s cantatas?

In Colorado, it never happened. I was afraid of my own shadow in the mountains, so I kept to sunny days (except for that one day with some thunderstorms, but whatever – they don’t make for good lighting). It happened a time or two in Wyoming, though I lacked as much winter flying as I would have liked. Spain? I believe I had a chance 3 or 4 times to see a muted overcast sky with snow beneath. Usually clouds were orographic or part of an inversion.

So that lends to the question…how the hell did I come up with this “classic” idea?

Western New York….the place where I was squeezed through the vagina at birth and took my initial flight lessons in the Cub. If one is unfortunate enough to visit while the weather is foul (most of the time), then an observant individual would note that the sun disappears for practically half the year. A relatively classic cycle of weather is as follows: storm system, cold front, brisk northwest wind, lake effect clouds behind it (no sun), maybe a bit of sun after lake effect abates, then a warm or occluded front preceding the next storm. It was in this precise window that winds would tend to be calm, pressure would begin to lower, skies would filter in mid-to-high clouds, and the air took on a certain stillness. No longer was it lashing rain, lashing wind from Canada, angry splashes of snow. Instead, it was a serene, reflective moment before the weather would go to shit again, and I tended to like it.

I have many positive memories of flying the Cub in this kind of weather, as it was either this weather cycle (warm front) or a tiny window of sun where I could fly. Then it was back to a mud pit of a short-field, crosswind grass strip where, as a new pilot, I couldn’t handle 30mph sideways winds which were common.

In circumstances out of New York, I am surprised how rare it is to get a moisturized, calm overcast sky in advance of a low pressure system that mimics these pleasant memories.

Bernese Alps.

“Sector blindness” is a reality in circumstances such as this. It is where a pilot does not notice the difference between snow and a cloud and crashes into the mountain turning it into a “story of fire and ice.”

The foothills in tranquil tones. I had to desaturate the blues out of the trees, which was something quite normal in the Northeast of the USA. On a cloudy day, treeless hills in winter would appear blue.

Looking into the Valais.

Humans on a glacier.

Early sunset tones with Mt. Blanc on the horizon.

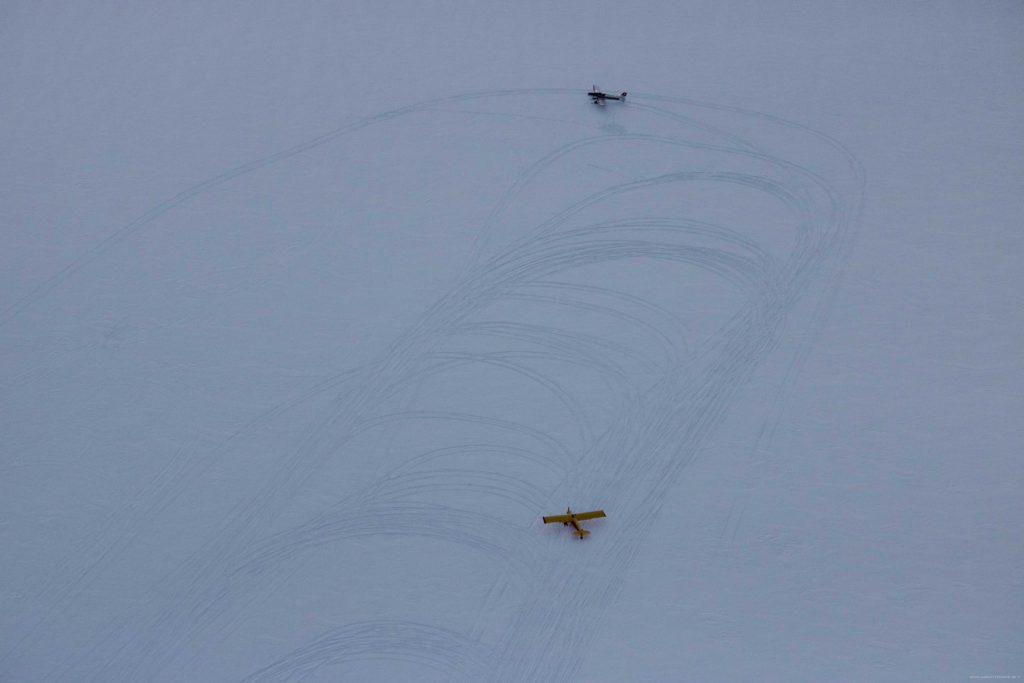

Airplanes on a glacier. Why don’t you do that with the Cub? I was quoted $35,000 for skis for the Cub, and $30,000 for the ski rating. To quote a British individual, “They can stick their skis where the sun doesn’t shine.”